Home → Women's Issues → Printer Friendly Version

Women's Issues

- 1. Women's Health Issues

- 2. Women with Disabilites

- 3. Reproductive Health

- 4. Preventive Health Issues

- 5. Disability Organizations for Women

1. Women's Health Issues

1.1. Osteoporosis and Spinal Cord Injury

By Jelena Svircev, MD,

assistant professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Washington.

Read the report or watch the video from this page.

What is Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis, or porous bone, is a disease in which the bones lose density, become weak and brittle, and are more likely to break.

People often think of bone as a static structure, or something dry and non-living. It's actually a very dynamic organ, constantly resorbing, developing and recreating new bone tissue. In osteoporosis, there is an imbalance between bone formation and bone resorption, leading to thinner, more fragile bones that can fracture easily.

Bony Anatomy

A little background in bony anatomy is helpful for understanding osteoporosis and risk of fractures in SCI.

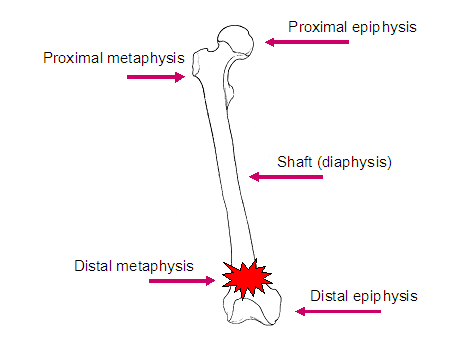

Long bones are made up of three primary areas (see illustration)

- Diaphysis, or midshaft of the bone.

- Epiphysis, or ends of the bone.

- Proximal (the end of the bone that is closest to the head of the body).

- Distal (the end of the bone that is farthest from the head of the body).

- Metaphysis, which lies next to the epiphysis.

When individuals with SCI sustain fractures, they typically occur in particular areas of the bones, often in the metaphysis or the distal epiphysis.

Bone itself has a number of different components.

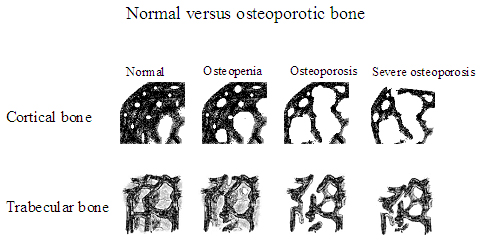

- Cortical bone, or compact bone, is highly organized and makes up about 80% of bone in the body.

- Trabecular bone, known as cancellous or spongy bone, makes up approximately 20% of all bone. Trabecular bone has very high bone turnover, meaning it is formed and resorbed at a higher rate than other bone.

Both types of bone become more porous and brittle as osteoporosis develops.

[Images courtesy of Susan Ott, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Washington.]

On the left [in the illustration above] is normal bone structure with a very intricate bony microarchitecture. As we move to the right we see that this microarchitecture has been destroyed, leading to a weaker bone.

Normal bone structure is defined as the peak bone mineral density achieved at about 20 years of age, but this varies by ethnicity and gender. Comparing bone density to this standard tells us whether a person has osteoporosis, and if so, how severe it is.

Osteoporosis and SCI

Osteoporosis is a common consequence of SCI. While the most common pattern of osteoporosis in the general population is in the post-menopausal female, who classically fractures in the vertebrae, the hips and the wrist, osteoporosis in SCI is quite different.

- Bone loss occurs below the level of the spinal cord injury, with preservation of bone mass above the level of the injury.

- Trabecular bone is more affected than cortical bone, and in particular trabecular bone of the distal (closer to the bottom end) femur (the thigh bone) and the proximal (closer to the top end) tibia (the shin bone). Studies vary, but generally there is about 30% to 40% decrease in bone density in the legs after SCI.

- Osteoporosis can be detected on x-ray as early as six weeks after injury. Most researchers feel that bone loss slows down and levels out around two years after injury, but some studies suggest bone loss continues to occur after that at a very slow rate. This issue remains controversial.

- The lumbar spine maintains normal or higher values of bone mineral density after SCI. Why does this occur? One theory suggests that the substantial weight-loading that comes from sitting in a wheelchair may stimulate bone building activity enough to maintain the bone mineral density in the spine. The non-weight bearing lower extremities don't have this stimulation and therefore lose bone mineral density.

- Injury level

- Individuals with tetraplegia have more bone loss because there's more area below the level of injury to be lost.

- Individuals with paraplegia usually have bone mineral density preserved in their upper extremities.

- In the bone that is affected, the severity of bone loss is the same both in paraplegia and tetraplegia.

- Extent of injury: Individuals with complete injuries have more bone loss than those with incomplete injuries.

- Spasticity may play a role in maintaining bone mass after SCI, due to muscle pulling on the bone, similar to the effect of weight-bearing.

- Duration of injury: The longer time since injury, the greater the bone loss is likely to be.

- Aging: People in the general population usually have some degree of bone mass loss as they age. But studies in the SCI population are quite controversial. Two studies comparing older and younger individuals with SCI found greater bone loss in the older groups (Kiratli 2000, Garland 2001), but others found that it was duration since injury rather that age that influenced the bone mass.

Fractures and SCI

As the bone mineral density decreases, the risk of fractures increases. The incidence of fractures of the lower limbs in SCI is high, from 1% to 34% of the SCI population. Most fractures occur not from injury, but from normal activities such as transferring. Sometimes people cannot recall any sort of incident, but just notice a symptom such as swelling that, upon examination, turns out to be due to fracture.

Causes of osteoporosis in SCI

- Disuse: lack of mechanical loading on the bone inhibits stimulation of bone-building cells.

- Disordered vasoregulation: sluggish blood flow to limbs may contribute to a decrease in bone mass.

- Poor nutritional status: inadequate consumption of a healthy, well balanced diet.

- Hormonal alterations (PTH, glucocorticoids, calcitonin): proteins in the body play a role in the maintenance of bony formation and resorption.

- Metabolic disturbances (tissue acidosis, alkaline phosphatase, hypercalcemia/hyercalciuria, hydroxyproline excretion): disturbance in metabolites and acidity of the blood can influence the balance of bony formation and resorption.

- Autonomic disregulation: impaired control by the self-regulating nervous system can lead to increased imbalance between bone formation and resorption.

Treatment of fractures in SCI

|

Treatment |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Conservative/ |

|

|

|

Surgical |

|

|

What is the best way to address fractures in individuals with SCI? (Here we are referring to lower extremity fractures in people with chronic SCI, since upper extremity fractures in chronic SCI and lower extremity fractures in acute SCI are treated similarly to the able-bodied population.)

Historically, we tended to favor conservative or non surgical treatment. More recently, some studies are suggesting that perhaps surgical treatments may be superior to conservative treatment in the treatment of fractures. The chart above outlines the advantages and disadvantages of both.

First and foremost we want to heal the fracture with minimal risk of complication and generally recommend avoiding surgical intervention. We prefer to use soft removable splints, since a plaster cast does not allow you to check the skin underneath for possible rubbing wounds that can't be felt. It is important to immobilize the fractured area as soon as possible.

In the past, practitioners didn't think it mattered whether a limb was shortened or deformed after healing in a person who did not ambulate. We no longer think this is acceptable. We need to assess all equipment and activities of daily living during healing and post healing. If a leg ends up in the wrong position as a result of surgery or inadequate follow-up, it may be in an altered position that causes increased pressure when sitting in the wheelchair. Our goal is to maintain pre-fracture functional status; we don't want someone to lose functional independence as a result of their fracture.

Medications for osteoporosis

- Calcitonin, a hormone, may prevent early bone resorption, but there's very limited research to support this. Calcium levels have been found to be normal in chronic SCI, so we don't generally recommend extra calcium intake in order to prevent osteoporosis unless someone is getting insufficient levels of calcium in their diet.

- Vitamin D supplementation or parathyroid hormone supplementation. Research results have been inconsistent. Some suggest that both of these substances are depressed in SCI and need supplementation, whereas others found that parathyroid hormone is normal and that vitamin D levels are elevated, in which case we shouldn't supplement.

- Bisphosphonates (etidronate, tiludronate, alendronate) are medications that strongly inhibit bone resorption, but again studies are inconclusive and didn't include large enough populations of people, so we cannot recommend their use in SCI.

Exercise and osteoporosis

Unfortunately, no functional exercise has been consistently demonstrated to be effective in preventing or treating osteoporosis in SCI. Both standing and Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) with cycle ergometry have been studied, but results so far haven't shown significant benefit. These activities do have other benefits, however. Standing, for example, can reduce spasticity, improve range of motion and circulation, and provide psychological improvements.

Recommendations

I always recommend that my patients return to as much activity and as large a variety of activity as possible, as long as they do not increase the risk for fractures.

What can we recommend for osteoporosis at this time?

- Consume a healthy diet, including 1000 to 1500 mg of calcium.

- Some people suggest that vitamin D supplementation should be considered for those individuals who live in the Pacific Northwest and may not get enough sun (a natural source of vitamin D) over the winter months. The recommended dose is generally 400 to 800 IU.

- Smoking, alcohol and caffeine contribute to osteoporosis. Individuals should quit smoking and try to limit their alcohol (to one or two drinks per day) and caffeine intake.

Avoid falls and situations that may increase the risk of fracture. This includes making sure that your equipment is safe, practicing good transfer technique, and keeping the environment safe. If you walk, remove throw rugs and other obstacles that may increase your chances of falling.

I am of the belief that it won't be one thing that will prevent or cure osteoporosis in SCI, but a combination of factors, such as medications along with some other modality or exercise. Overall, as always in SCI, there are many avenues of research that need to be explored.

References

- Garland DE, Adkins RH, Steward CA, Ashford R, Vigil D. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1195-1200.

- Kiratli JB. Immobilization Osteopenia. Osteoporosis, Second Edition, Volume 2. 2001 Academic Press.207-227.

- Sabo D, Blaich S, Wenz W, Hohmann M, Loew M, Gerner HJ. Osteoporosis in patients with paralysis after spinal cord injury: A cross sectional study in 46 male patients with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:75-78.

- Szollar SM, Martin EM, Sartoris DJ, Parthemore JG, Deftos LJ. Bone mineral density and indexes of bone metabolism in SCI.Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998 Jan-Feb;77(1):28-35.

- Zehnder Y, Lüthi M, Michel D, Knecht H, Perrelet R, Neto I, Kraenzlin M, Zäch G, Lippuner K. Long-term changes in bone metabolism, bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasound parameters, and fracture incidence after SCI: a cross-sectional observational study in 100 paraplegic men. Osteoporos Int. 2004 Mar;15(3):180-9. Epub 2004 Jan 13

- Osteoporosis and bone physiology: http://courses.washington.edu/bonephys/. Educational site for physicians and patients, run by Susan Ott, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Washington.

1.2. Menopause

What is menopause?

Menopause is the point in time when a woman's menstrual periods stop. Some people call the years leading up to a woman's last period "menopause," but that time actually is perimenopause (PER-ee-MEN-oh-pawz).

Periods can stop for a while and then start again, so a woman is considered to have been through menopause only after a full year without periods. (There also can't be some other reason for the periods stopping like being sick or pregnant.) After menopause, a woman no longer can get pregnant. It is common to experience symptoms such as hot flashes in the time around menopause.

The average age of menopause is 51, but for some women it happens in their 40s or later in their 50s. Sometimes called "the change of life," menopause is a normal part of life.

What is perimenopause?

Perimenopause (PER-ee-MEN-oh-pawz), which is sometimes called "the menopausal transition," is the time leading up to a woman's last period. During this time a woman will have changes in her levels of the hormones estrogen (ES-truh-jin) and progesterone (proh-JES-tuh-RONE). These changes may cause symptoms like hot flashes. Some symptoms can last for months or years after a woman's period stops. After menopause, a woman is in postmenopause, which lasts the rest of her life.

What symptoms might I have before and after menopause?

Do not assume that if you miss a couple of periods the cause is menopause. See your doctor to find out if pregnancy or a health problem could be the cause. Also see your doctor if you have not had a period for a year and then start "spotting."

The hormone changes that happen around menopause affect every woman differently. Also, symptoms sometimes are not caused by menopause but by other aspects of aging instead.

Some changes that might start in the years around menopause include:

- Irregular periods. Your periods may:

- Come more often or less often

- Last more days or fewer

- Be lighter or heavier

- Hot flashes (or flushes). These can cause:

- Sudden feelings of heat all over or in the upper part of your body

- Flushing of your face and neck

- Red blotches on your chest, back, and arms

- Heavy sweating and cold shivering after the flash

- Trouble sleeping. You may have:

- Trouble sleeping through the night

- Night sweats (hot flashes that make you sweat while you sleep)

- Vaginal and urinary problems. Changing hormone levels can lead to:

- Drier and thinner vaginal tissue, which can make sex uncomfortable

- More infections in the vagina

- More urinary tract infections

- Not being able to hold your urine long enough to get to the bathroom (urinary incontinence)

- Mood changes. You might:

- Have mood swings (which are not the same as depression)

- Cry more often

- Feel crabby

- Changing feelings about sex. You might:

- Feel less interested in sex

- Feel more comfortable with your sexuality

- Other changes. Some other possible changes at this time (either from lower levels of hormones or just from getting older) include:

- Forgetfulness or trouble focusing

- Losing muscle, gaining fat, and having a larger waist

- Feeling stiff or achy

How will I know when I am nearing menopause?

Symptoms, a physical exam, and your medical history can provide clues that you are in perimenopause. Your doctor also could test the amount of hormones in your blood. But hormones go up and down during your menstrual cycle, so these tests alone can't tell for sure that you have gone through menopause or are getting close to it.

How can I manage symptoms of menopause?

It is not necessary to get treatment for your symptoms unless they are bothering you. You can learn about simple lifestyle changes that may help with symptoms, and some symptoms will go away on their own. If you're interested in medical treatments like menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), ask your doctor about the possible risks and benefits.

Here are some ways to deal with symptoms:

Hot flashes

- Try to avoid things that may trigger hot flashes, like spicy foods, alcohol, caffeine, stress, or being in a hot place.

- Dress in layers, and remove some when you feel a flash starting.

- Use a fan in your home or workplace.

- Try taking slow, deep breaths when a hot flash starts.

- If you still get periods, ask your doctor about low-dose oral contraceptives (birth control pills), which may help.

- Some women can take menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), which can be very effective in treating hot flashes and night sweats.

- If MHT is not an option, your doctor may prescribe medications that usually are used for other conditions, like epilepsy, depression, and high blood pressure, but that have been shown to help with hot flashes.

Vaginal dryness

- A water-based, over-the-counter vaginal lubricant like K-Y Jelly can help make sex more comfortable.

- An over-the-counter vaginal moisturizer like Replens can help keep needed moisture in your vagina.

- The most effective treatment may be MHT if the dryness is severe. But if dryness is the only reason for considering MHT, vaginal estrogen products like creams generally are a better choice.

Problems sleeping

- Be physically active (but not too close to bedtime, since exercise might make you more awake).

- Avoid large meals, smoking, and working right before bed. Avoid caffeine after noon.

- Keep your bedroom dark, quiet, and cool. Use your bedroom only for sleep and sex.

- Avoid napping during the day.

- Try to go to bed and get up at the same times every day.

- If you can't get to sleep, get up and read until you're tired.

- If hot flashes are the cause of sleep problems, treating the hot flashes usually will help.

Mood swings

- Try getting enough sleep and staying physically active to feel your best.

- Learn ways to deal with stress. Our fact sheet on "Stress and your health" has helpful tips.

- Talk to your doctor to see if you may have depression, which is a serious illness.

- Consider seeing a therapist or joining a support group.

- If you are using MHT for hot flashes or another menopause symptom, your mood swings may get better too.

Memory problems

- Getting enough sleep and keeping physically active may help.

- If forgetfulness or other mental problems are affecting your daily life, see your doctor.

Urinary incontinence

- Ask your doctor about treatments, including medicines, behavioral changes, certain devices, and surgery.

Does menopause cause bone loss?

Lower estrogen around the time of menopause leads to bone loss in women. Bone loss can cause bones to weaken, which can cause bones to break more easily. When bones weaken a lot, the condition is called osteoporosis (OSS-tee-oh-puh-ROH-suhss).

To keep your bones strong, women need weight-bearing exercise, such as walking, climbing stairs, or using weights. You can also protect bone health by eating foods rich in calcium and vitamin D, or if needed, taking calcium and vitamin D supplements. Not smoking also helps protect your bones.

Ask your doctor if you need a bone density test. Your doctor can also suggest ways to prevent or treat osteoporosis.

Does menopause raise my chances of getting cardiovascular disease?

Yes. After menopause, women are more likely to have cardiovascular (kar-dee-oh-VAS-kuh-lur) problems, like heart attacks and strokes. Changes in estrogen levels may be part of the cause, but so is getting older. That's because as you get older, you may gain weight and develop other health problems that increase your risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Ask your doctor about important tests like those for cholesterol and high blood pressure. Discuss ways to prevent CVD. The following lifestyle changes also can help prevent CVD:

- Not smoking and avoiding secondhand smoke

- Exercising

- Following a healthy diet

Can menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) help treat my symptoms?

MHT, which used to be called hormone replacement therapy (HRT), involves taking the hormones estrogen and progesterone. (Women who don't have a uterus anymore take just estrogen). MHT can be very good at relieving moderate to severe menopausal symptoms and preventing bone loss. But MHT also has some risks, especially if used for a long time.

MHT can help with menopause by:

- Reducing hot flashes and night sweats, and related problems such as poor sleep and irritability

- Treating vaginal symptoms, such as dryness and discomfort, and related problems, such as pain during sex

- Slowing bone loss

- Possibly easing mood swings and mild depressive mood

For some women, MHT may increase their chance of:

- Blood clots

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Breast cancer

- Gall bladder disease

Research into the risks and benefits of MHT continues. For example, a recent study suggests that the low-dose patch form of MHT may not have the possible risk of stroke that other forms can have. Talk with your doctor about the positives and negatives of MHT based on your medical history and age. Keep in mind, too, that you may have symptoms when you stop MHT. You can also ask about other treatment options. Lower-dose estrogen products (vaginal creams, rings, and tablets) are a good choice if you are bothered only by vaginal symptoms, for example. And other drugs may help with bone loss.

If you choose MHT, experts recommend that you:

- Use it at the lowest dose that helps

- Use it for the shortest time needed

If you take MHT, call your doctor if you develop any of the following side effects:

- Vaginal bleeding

- Bloating

- Breast tenderness or swelling

- Headaches

- Mood changes

- Nausea

Who should not take MHT for menopause?

Women who:

- Think they are pregnant

- Have problems with undiagnosed vaginal bleeding

- Have had certain kinds of cancers (such as breast or uterine cancer)

- Have had a stroke or heart attack

- Have had blood clots

- Have liver disease

- Have heart disease

Can MHT prevent heart disease or Alzheimer's disease?

A major study called the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) has looked at the effects of MHT on heart disease and other health concerns. It has explored many questions relating to MHT, including whether MHT's effects are different depending on when a woman starts it. Learn more about MHT research results ![]() .

.

Future research may tell experts even more about MHT. For now, MHT should not be used to prevent heart disease, memory loss, dementia, or Alzheimer's disease. MHT sometimes is used to treat bone loss and menopausal symptoms. Learn more in Can menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) help my symptoms?

Are there natural treatments for my symptoms?

Some women try herbs or other products that come from plants to help relieve hot flashes. These include:

- Soy. Soy contains phytoestrogens (FEYE-toh-ESS-truh-juhns). These are substances from a plant that may act like the estrogen your body makes. There is no clear proof that soy or other sources of phytoestrogens make hot flashes better. And the risks of taking soy products like pills and powders are not known. If you are going to try soy, the best sources are foods such as tofu, tempeh, soymilk, and soy nuts.

- Other sources of phytoestrogens. These include herbs such as black cohosh, wild yam, dong quai, and valerian root. There is not enough evidence that these herbs or pills or creams containing these herbs help with hot flashes. Also, not enough is known about the risks of using these products.

Make sure to discuss any natural or herbal products with your doctor before taking them. It's also important to tell your doctor about all medicines you are taking. Some plant products or foods can be harmful when combined with certain medications.

What is "bioidentical" hormone therapy?

Bioidentical hormone therapy (BHT) means manmade hormones that are the same as the hormones the body makes. There are several prescription BHT products that are well-tested and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Often, people use the term "BHT" to mean medications that are custom-made by a pharmacist for a specific patient based on a doctor's order. These custom-made products are also sometimes called bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT). Despite claims, there is no proof that these products are better or safer than drugs approved by the FDA. Also, many insurance and prescription programs do not pay for these drugs because they are viewed as experimental.

How much physical activity do I need as I approach menopause?

Physical activity helps many areas of your life, including mood, sleep, and heart health. Aim for:

- At least 2 hours and 30 minutes a week of moderate aerobic physical activity or 1 hour and 15 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity or some combination of the two

- Exercises that build muscle strength on two days each week

If you are not able to follow these guidelines, be as physically active as you can. Your doctor can help you decide what's right for you.

Do I need a special diet as I approach menopause?

A balanced diet will give you most of what your body needs to stay healthy. Here are a few special points to consider:

- Older people need just as many nutrients but tend to need fewer calories for energy. Learn about eating healthy after 50

.

. - Women over 50 need 2.4 micrograms (mcg) of vitamin B12 and 1.5 milligrams of vitamin B6 each day. Ask your doctor if you need a vitamin supplement.

- After menopause, a woman's calcium needs go up to maintain bone health. Women 51 and older should get 1,200 milligrams (mg) of calcium each day. Vitamin D also is important to bone health. Women 51 to 70 should get 600 international units (IU) of vitamin D each day. Women ages 71 and older need 800 IU of vitamin D each day.

- Women past menopause who are still having vaginal bleeding because they are using menopausal hormone therapy might need extra iron.

I'm having a hysterectomy soon. Will this cause menopause?

A woman who has a hysterectomy (his-tur-EK-tuh-mee) but keeps her ovaries does not have menopause right away. Because your uterus is removed, you no longer have periods and cannot get pregnant. But your ovaries might still make hormones, so you might not have other signs of menopause. You may have hot flashes because the surgery may affect the blood supply to the ovaries. Later on, you might have natural menopause a year or two earlier than usually expected.

A woman who has both ovaries removed at the same time that the hysterectomy is done has menopause right away. Having both ovaries removed is called a bilateral oophorectomy (OH-uh-fuh-REK-tuh-mee). Women who have this operation no longer have periods and may have menopausal symptoms right away. Because your hormones drop quickly, your symptoms may be stronger than with natural menopause. If you are having this surgery, ask your doctor about how to manage your symptoms.

Menopause that is caused by surgery also puts you at risk for certain conditions, such as bone loss and heart disease. Ask your doctor about possible steps, including MHT, to help prevent these problems.

What if I have symptoms of menopause before age 40?

Some women have symptoms of menopause and stop having their periods much earlier than expected. This can happen for no clear reason, or it can be caused by:

- Medical treatments, such as surgery to remove the ovaries

- Cancer treatments that damage the ovaries such as chemotherapy or radiation to the pelvic area although menopause does not always occur

- An immune system problem in which a woman's own body cells attack her ovaries

When menopause comes early on its own, it sometimes has been called "premature menopause" or "premature ovarian failure." A better term is "primary ovarian insufficiency," which describes the decreased activity in the ovaries. In some cases, women have ovaries that still make hormones from time to time, and their menstrual periods return. Some women can even become pregnant after the diagnosis.

For women who want to have children and can't, early menopause can be a source of great distress. Women who want to become mothers can talk with their doctors about other options, such as donor egg programs or adoption.

Early menopause raises your risk of certain health problems, such as heart disease and osteoporosis. Talk to your doctor about ways to protect your health. You might ask about menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). Some researchers think the risks of MHT for younger women might be smaller and the benefits greater than for women who begin MHT at or after the typical age of menopause.

Let your doctor know if you are younger than 40 and have symptoms of menopause.

More information on menopause and menopause treatments

For more information about menopause and menopause treatments, call womenshealth.gov at 800-994-9662 (TDD: 888-220-5446) or contact the following organizations:

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS

Phone: 888-463-6332 - National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Phone: 888-644-6226 (TDD: 866-464-3615) - National Institute on Aging, NIH, HHS

Phone: 301-496-1752 (TDD: 800-222-2225) - The Hormone Foundation

Phone: 800-467-6663 - The North American Menopause Society

Phone: 440-442-7550

The information on our website is provided by the U.S. federal government and is in the public domain. This public information is not copyrighted and may be reproduced without permission, though citation of each source is appreciated.

Menopause and menopause treatments fact sheet was reviewed by:

Songhai Barclift, M.D., F.A.C.O.G.

Lieutenant Commander

U.S. Public Health Service

Health Resources and Services Administration

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Lisa M. Jones, M.D., M.A., F.A.C.O.G.

Obstetrician-Gynecologist

Greater New Bedford Community Health Center

Providence, Rhode Island

Content last updated September 28, 2010.

1.3. Aging with SCI

What Women Need to Know About Aging with SCI

This article is from the Pushin' On Newsletter, Vol 18[1], Winter, 2000.

What Women Need to Know about Aging with SCI

by Laura Mosqueda, M.D.

Women who have a spinal cord injury (SCI) need to prepare for the future when thinking about health care. Many people with SCI, as well as their physicians, operate in the "acute" mode. In other words they deal with problems and issues as they arise. Not enough people make plans for a healthy future. Thanks to better health care, self-advocacy and improved social programs a woman with SCI must plan to live into old age.

Thinking about the future means thinking about preventive health. This is important to all women regardless of disability status, but it is very important for women with SCI to be aware of their special health concerns. There are several types of preventive health care. Primary prevention refers to ways that may stop a person from getting a disease. An example of this is immunization for influenza, or flu shot. It is designed to actually prevent people from getting the flu. Secondary prevention refers to ways that may help doctors detect a treatable disease at an early stage, before it becomes a serious problem. An example of this is a mammogram. It will not prevent breast cancer, but mammograms can detect breast cancer at an early stage so that it may be successfully treated.

Immunizations

It is certainly important for everyone with SCI to remain up-to-date on immunizations. This includes the flu shot every year and tetanus shot every 10 years. It is also important for people with SCI to get a shot for protection against a particular type of pneumonia (pneumococcal pneumonia). Many physicians think that this protection is for the elderly or people with lung disease, but people with SCI need to remind their doctor that they, too, are at risk for pneumonia. This is because of the weakened respiratory function that occurs after injury.

Pap Smears

Pap smears are used to detect cancer of the cervix. They may even detect changes in cells before they turn into cancer. Some women are at higher risk of developing cervical cancer than others. Women who began having sexual intercourse at an early age and/or who have multiple sexual partners are at a higher risk. Women at higher risk should be screened every two years. Those women who are sexually active but not at high risk should be screened every three years if they have already had two or three normal smears. After the age of 65, further screening is not needed unless high-risk behavior such as multiple sexual partners continues. Also, women who have undergone a hysterectomy (the surgical removal of the uterus) do not need to be screened unless the surgery was performed because of cervical cancer.

Women with spinal cord injury may need to plan ahead for the Pap smear. Some doctors' offices and rehabilitation facilities may be accessible and have adjustable examination tables. But most offices are not easily accessible. Some are not accessible at all! It can be a challenge for women with SCI to find an accessible office. There can be problems with transferring on and off the examination table. It may be difficult maintaining the proper position for the Pap smear. Women can help by taking an active role in guiding the physician and office staff in the best methods for assisting with transfers, positioning, and techniques for a more comfortable exam.

Mammograms

It is important to make the same accessibility preparations when getting a mammogram. There is a lot of controversy over the appropriate screening guidelines for mammograms. Most agencies agree that all women between the ages of 50 and 69 years should be screened once a year. Some doctors encourage women to have their first mammogram at age 40.

There are some factors to consider that may increase a woman's risk of breast cancer:

1 a history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative (a mother or sister), particularly if the cancer developed before menopause;

2 having no children or having the first child at an older age; and

3 certain types of benign (non-cancerous) breast disease that can be seen on a mammogram.

Some women with SCI have limited use of their hands. This can make breast self-examinations difficult. It is even more important that women with this difficulty have regular breast exams and mammograms as a routine part of a your health care plan.

Osteoporosis

All women will experience a gradual loss of bone density after the age of 30. At the time of menopause, there is a rather sudden increase in the loss of bone density. This may cause some women to develop osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a disease that thins and weakens bones to the point where they break easily - especially bones in the hip, spine, and wrist.1

Women with spinal cord injury need to be especially cautious in preventing and treating low bone density. For the first few months following injury, there is a loss of bone density in many parts of the skeleton. This loss is due in part to the body's inability to bear weight on some bones. If a woman has a spinal cord injury at the age of 25, what will happen when she turns 50 and experiences menopause? There may be another dramatic loss of bone. This puts women with SCI at an even higher risk of breaking a bone.

Osteoporosis is related to a lack of estrogen and may be prevented by taking estrogen, a hormone replacement therapy. The issue of hormone replacement therapy and prevention of osteoporosis is something that women with SCI need to discuss with their doctor.

Conclusion

It is important for women with spinal cord injury to develop a partnership with their doctor and plan for a healthy future. Remind your doctor to treat health care issues that may be neglected in the acute setting. Make sure to practice primary and secondary prevention of conditions by getting regular immunizations, Pap smears and mammograms. Finally, talk with your doctor about what you can do to reduce the affects of osteoporosis.

Remember, better health care today can mean better health tomorrow.

Resources

1 http://www.nih.gov/nia/health/pubpub/osteo.htm

Laura Mosqueda, MD is Director of Geriatrics and Associate Professor of Clinical Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine College of Medicine. She is Co-Director of the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Aging with A Disability, Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center, Downey, CA. This work was supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, US Dept of Education grant #H133B980024.

2. Women with Disabilites

2.1. Women and Spinal Cord Injury

The SCI Forum video "Women and Spinal Cord Injury" has been posted on Northwest Regional Spinal Cord Injury System website.

Women with spinal cord injury are a minority within a minority. Because they make up only about 25% of all people with spinal cord injuries, they can often feel that their needs are not addressed, and they may have a hard time getting answers to their specific questions about health issues unique to their gender. In this panel discussion, five women with spinal cord injuries share their experiences and offer useful information about staying healthy as a female living with a spinal cord injury. Also on the panel is Erica Bechtel, MD, SCI Fellow at the Puget Sound VA Medical Center. The discussion is moderated by UW rehabilitation medicine psychologist Jeanne Hoffman, PhD.

Check out all of Northwest Regional Spinal Cord Injury System videos at http://sci.washington.edu/videos.

2.2. Women and Change

Reflecting on change is not an easy endeavor. Life is change. With that in mind, New Mobility set out to get a glimpse of how the experience of women with disabilities has changed in the past few decades--both politically and personally. We talked to many women, from twentysomethings to seventysomethings, from all over the country and with all sorts of backgrounds.

A Ramp to the Moon by Melina Fatsiou-Cowan

|

Mona Hughes, 58, knows what it was like to grow up in an era when women with disabilities were expected to remain in the shadows. "We were a generation of individuals with disabilities raised with the idea of don't make waves. Don't complain. Be grateful for what you have." By contrast, says Hughes, a polio survivor and author of Women and Disabilities: It Isn't Us and Them, younger women are much less willing to accept that attitude.

Hughes and other experienced advocates see change on the horizon as young women with disabilities deal with emerging issues such as caregiver shortages and eugenics, as well as the continuing struggle for more self-determination. "I'm very impressed with young disabled women," says Marsha Saxton, 50, a professor of disability studies at University of California, Berkeley, who has spina bifida. "I work with disabled college students, and they are much more sophisticated than previous generations."

Some change will also likely come from aging baby boomers, who could have a huge impact on the intangible aspects of disability. Polio survivor Carol Gill, 52, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and director of the Chicago Center for Disability Research, anticipates that boomers will redefine aging, redefine beauty and redefine attitudes toward disability.

"The isolation imposed on [women with disabilities] keeps them oppressed in so many ways. The only way we're going to make any impact is one-on-one in the independent living centers, the community health centers, the YWCAs."

-- Margaret Nosek

|

"I think we're on the threshold of real change," says longtime MSer Dianne Piastro, 62, a former syndicated columnist on disability who designed the first disability course for California State University, Long Beach. We already have many laws on the books, she adds, but the next generation must be ready to take over. "We have to have enough people who are able to get out there and make the changes."

While experienced women bring their personal involvement and knowledge of disability history to the fore, younger women seem to be motivated by an innate desire for change. "They're a little more impatient," says Hughes. "They get impatient hearing 'no.'"

They may not like hearing no, but they are certainly saying no: no to the societal attitudes and messages that have devalued them and told them they aren't beautiful, that they aren't normal, that they will be lucky if a man loves them, and that they shouldn't have babies.

The Road to Self-Esteem

We live in a hyper-body-conscious society where women struggle to keep themselves looking "perfect," and women with disabilities have not been excluded from that stress.

Studies of adolescents with disabilities found that their main concerns were the typical teen girl points of angst--dating and breast size--says Margaret Nosek, 48, head of the Center for Research on Women with Disabilities and a professor at Houston's Baylor College of Medicine. "So we absorb all the same stuff, but in addition we've got a really strong stigmatized factor," says Nosek, who has spinal muscular atrophy.

You might imagine that would be hell on the collective self-esteem. But a National Study of Women with Physical Disabilities in 1997 published by Nosek's center found that 78 percent of the women surveyed reported moderately high or high self-esteem, though generally lower self-esteem than their nondisabled counterparts. However, the researchers also found it interesting that the levels of self-esteem didn't necessarily correlate to the disability; rather it was a combination of factors--such as whether the women were happy with their activities or in a relationship--that made the real difference.

Since it was the first major study of women with disabilities, it's difficult to say how the figures compare to previous decades, but researchers are starting to look at the issue more in-depth. Gill and Joy Weeber, 45, a polio survivor, student and disability activist in North Carolina, are studying how people with disabilities develop a positive sense of self.

Although they are only halfway into the study, Gill and Weeber are finding that people with disabilities develop their identity and self-concept in ways similar to other minority groups--by being part of a community and getting validation from that community. However, there is a twist when it comes to this particular minority group. "One of the surprises so far is that for people with disabilities, that validation frequently happens from other disabled peers," Gill says. "What we're finding in women with disabilities is that they're talking about having a girlfriend who has a disability or has a lot of understanding of the issues of diversity." And it's that friend who gives them the validating messages.

After contracting polio, Joy Weeber (shown with her late husband Ron Mace) was taught to ignore and "overcome" pain. Today, however, she listens to her body.

|

That's not to say that the dominant culture has no role. For Melina Fatsiou-Cowan, 45, a painter from Greece who moved to Alabama with her husband 10 years ago, validation came from her new neighbors. She was born with spinal muscular atrophy--a source of pity in her native country--and was surprised by how Americans were so much less concerned with her disability. "I had the shock of my life because people here accept disability much more than they accept it in my country," Fatsiou-Cowan says. Her new friends were more interested in her being Greek than in her being a wheelchair user.

Now Fatsiou-Cowan's work--beautiful watercolor paintings of women with disabilities--has been, in turn, a source of affirmation for many other women. Gill says she tells many women about Fatsiou-Cowan's Web site--www.disabilityculture.org/melina--which shows several of her paintings of women's beautiful twisted bodies. "When they see her art, they are overwhelmed and so excited," Gill says. "It is immediately validating."

Ironically, Gill says that the messages of invalidation often come from those closest to women--their families. "I hear a lot in my research from women that it's their own families who tell them that no man will ever love you," Gill says. "It's their own family that says don't think about children. It's their own family that tells them try to walk straighter, you look funny, or don't wear a low-cut blouse because your chest doesn't look good. Those are messages that are not purposely denigrating, but they are messages of implicit devaluation."

Another factor in the self-esteem picture is isolation. Many women with disabilities are poor and marginalized and have little ability to interact with the people best able to validate them, Nosek says. "The isolation that is imposed on them keeps them oppressed in so many ways." Because of this, she says the most rewarding aspect of her work is connecting with women individually. "The only way we're going to make any impact in the disability scene is one-on-one in the independent living centers, the community health centers, the YWCAs," Nosek says.

"I encounter a great number of women [with disabilities] who are connected with lovers and partners, same sex or opposite. And it shows me that love really does conquer all."

-- Carol Gill

|

This kind of interaction is key, agrees Gill. "When you look at what women with disabilities have managed to do in terms of their own networking, their own activism, their speaking out, their own critiquing of values and slowly joining forces with other minority women in the women's movement, that's exciting. That's where it's hopeful."

And this is happening: Young women are getting together and embracing their whole selves. Piastro, who has many young women with disabilities in her courses, is optimistic. "I have seen them embrace their disability--integrate it into their identity," she says.

Reclaiming the Body

While many older women are still saddled with conceptions of society that they internalized--like that they don't measure up physically--younger women are starting to reject those messages.

"Women in general get a lot of bogus information on how they should look," says Naomi Ortiz, 22. "It doesn't freak me out anymore. I'm not scared about getting wrinkles and fat. To me, what matters is whether or not I'm doing something worthwhile."

That doesn't mean it's too late for women from other generations to revise their body image. Writer Lorie Levison, 49, describes her struggle to forge past the concept of body image to the idea of body innage--and assert her right to enjoy being in the body she has.

Nosek faced a changing body image when she got a tracheotomy. "Now I have this tube sticking out of my throat," she says. "It's very embarrassing." But, she adds, "I'm dressing much sexier--I'm compensating for the tube." Yet the idea is not to hide the latest sign of disability, but to accept and integrate it. "Some of my friends get me upset," she explains. "One friend came over and brought all these different scarves [to cover the tube]. I don't want to wear scarves!"

Weeber, who had polio as a child, talks about feeling disconnected from her body in reaction to years of surgeries and rehab. In the process, her mind "separated" from her body, just so she could deal with the loss of control, she says. She experienced a reunion with her body when the kitchen cabinets fell off the wall and onto her 15 years ago--she subsequently happened upon a physical therapist who understood how she was alienated from her physical self.

Carmen Jones gave birth to her son, Marcus, without a C-section because her doctor learned there was no need for one.

|

"In the process of recovering from the accident, I found healers who helped me reintegrate who I was," she says. From there, she took back control of her body, started learning self-care and how to nurture her body rather than trying to dominate it. "I had been brainwashed by the rehab agenda to never listen to the body's messages about pain--that it's mind over matter. Don't listen to the pain; you just plow through the pain." Now, she listens to the signals when her body's tired, instead of pushing it to perform. "That process taught me to trust again," she says. "I hadn't trusted any adult from age 10 to 30."

Similarly, NM's associate editor, Josie Byzek, 34, has come up with a personal mantra for dealing with MS: My body is not the enemy. No matter what happens, I will love my body and I will live as fully within my body as I can.

"With MS," she says, "it's the not knowing what's going to happen next that can really get to me, and I have to be on guard against trying to mentally separate myself from my body. It's not my body's fault it picked up a disease and it's not my fault that I can't make it better."

Relationships:

New Expectations

Once upon a time, women with disabilities--particularly those who use wheelchairs--weren't expected to date or have sex or get married. While that attitude has definitely changed in recent years, romantic opportunities are still much harder for women with disabilities to come by than for nondisabled women. According to the national survey in 1997, 58 percent of the women with disabilities surveyed were single, compared to 45 percent of the women without disabilities.

Other studies have found that men with disabilities are more likely to marry than their female counterparts. "It sounds depressing," Gill says. "I think there are few opportunities for women being regarded as attractive and strong. However, I encounter a great number of women who are connected with lovers and partners, same sex or opposite. And it shows me that love really does conquer all."

And attitudes are changing from generation to generation. Ruth Brenyo, 78, had polio at 2 and married at 46. She wasn't sure she wanted to at the time--as an accessibility activist and one of the original organizers of Open Doors for the Handicapped of Pennsylvania, which began in 1957, she had a busy life. But he was a nice man, older, and already had children. Besides, she thought at the time, it might be her only chance to tie the knot: "There are not many people who want to marry a woman in a wheelchair."

The younger women interviewed were more blasé in their attitudes about relationships, assuming they would have them. Ortiz, a student at the University of Arizona in Tucson, has had two semi-serious relationships. And if she doesn't go for lifelong commitment, it won't necessarily be because of her disability, arthrogryposis. "As far as getting married, I think it's more my personality than my disability that limits me, which is OK," she says.

The Joy of Motherhood

If women with disabilities weren't expected to marry a few decades ago, they certainly weren't expected to have babies and raise families of their own. Brenyo recalls that her gynecologist didn't talk to her about options, but merely taught her how not to get pregnant. "He said I shouldn't have any children because my lower extremities weren't developed," she says. "He thought it wouldn't be good for my health."

"I think we're on the threshold of real change. ...[But] We have to have enough people who are able to get out there and make the changes."

-- Dianne Piastro

|

Consider the difference now. Carmen Jones, 35--who was one week away from her due date for her first child when she was interviewed for this article in July--at first thought she would have to get a Caesarean section. But her doctor, a specialist in high-risk babies, told her that women with spinal cord injuries have vaginal deliveries all the time.

But Jones' experience is not the norm. When Kathy Kusler, 35, was pregnant with her first child, her Ob/Gyn in New Mexico didn't have a lot of experience treating women with spinal cord injuries. But Kusler, C7-T1, dug up some articles on the subject and took them to her doctor. They discussed the information, considered options and decided not to do an epidural. The delivery went fine.

On the one hand, it might seem alarming that Kusler had to educate her doctor. However, it is heartening to many women, including Saxton, that the physician actually listened to her. That a doctor was willing to admit he didn't know everything and really hear his patient is a breakthrough, she says. Kusler's experience illustrates how women from younger generations have become more empowered to steer their own lives. "Young women have taken a quantum leap in terms of seeing themselves as active consumers of health care and using knowledge and information," Saxton says.

While the medical community and society at large may be more accepting of women with spinal cord injuries having children, there is a darker idea that is beginning to emerge: eugenics, or selective breeding. It may sound like something from a dystopia, but it's a concept that has already seeped into our collective consciousness.

Sarah Triano has felt it firsthand. A 26-year-old student at the University of Illinois at Chicago and co-founder of the National Disabled Students Union, Triano has a non-apparent genetic disability, which she chooses not to reveal. Because her disability could be passed on, she has heard the message over and over again that she should opt not to have children. "The expectation is that I should not have kids, and the responsible thing to do is not contaminate the gene pool," Triano says.

Generation Next

While the changes in the past few decades have been mostly positive, Nosek points out that many things have not changed enough. Younger generations have their work cut out for them: Women with disabilities are still disproportionately poor and unemployed, they still suffer discrimination and negative stereotyping and they are still grappling with isolation.

But there are some real reasons for hope, she adds. "It's really important to make the point that attitudes are changing," Nosek says. She thinks young women will build on this fledgling empowerment. "That's where the change will happen," she says. "If we can figure out how to take control of our lives, then a woman's attitude about herself and her disability can change."

Gill sees additional hope in the mainstream women's movement, which traditionally has not recognized women with disabilities. As the organizations mature, they become more understanding that the issues of all women--with disabilities or not--are the same.

"I hope that at the very beginning of their lives that women can begin to realize that disability, like everything different, is part of life and women's lives," Gill says. "Hopefully, women can be increasingly surrounded by images that say, 'It's OK to function differently. It's OK. We who've gone before you paved the way to make you feel proud.'"

2.3. Center for Research on Women with Disabilities

Mission Statement

The mission of the Center for Research on Women with Disabilities (CROWD) is to promote, develop, and disseminate information to improve the health and expand the life choices of women with disabilities. The faculty and staff accomplishes this by working with a consortium of local and national research collaborators, medical advisors, and consumer advisors. CROWD offers montly newsletters, blogs, and more.

Topics they have investigated include:

- Sexuality and reproductive health

- Self-esteem and other topics related to psychosocial health

- Health behaviors, including weight management, physical activity, and smoking cessation

- Secondary conditions

- Access to health care

- Violence and abuse

Contact Information:

Center for Research on Women with Disabilities (CROWD)

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Baylor College of Medicine

One Baylor Plaza, BCM 635

Houston, TX 77030

Telephone: SHARE

Email: crowd@BCM.edu

Telephone: 832-819-0232

3. Reproductive Health

3.1. Reproductive Health for Women with Spinal Cord Injury (Video)

Reproductive Health for Women with Spinal Cord Injury

Video Series

- Part I - The Gynecological Examination - 1997 (30 min)

Educates healthcare providers on how to safely and comfortably manage the annual GYN exam, breat self-exams and mammograms and menstrual management.

- Part II - Pregnancy & Delivery - 2003

Watch now in streaming Real Media.

Producer: UAB RRTC on Secondary Complications of SCI & Office of Research Services

3.2. Sexuality for Women with Spinal Cord Injury

Sexuality for Women with Spinal Cord Injury

Sexuality

Sexuality is an expression of one's self as a woman or man. It is intimate in nature, which means it is personal and private. Sexuality is commonly expressed through physical and emotional closeness. Most people consider sexual activity as a means to express physical intimacy. However, physical intimacy is more than sexual intercourse. Holding hands, hugging and kissing are good examples of ways to express physical intimacy. Likewise, emotional intimacy is more than feelings that result from physical contact. Emotional intimacy can be a connection with one's self that results in feelings of self-satisfaction, confidence and self-worth. It may also be a feeling of trust in another person and an openness to share private thoughts and feelings.

After Spinal Cord Injury

As a woman with spinal cord injury (SCI), you will discover that sexuality is still an important part of your life. It may take some time for a newly injured woman to become comfortable with her body and resume natural feelings of sexuality. Healthy adjustment begins with knowing the facts about the impact of SCI on sexual issues.

Sexual Function

In actuality, there are few physiological changes after injury that prevent women from engaging in sexual activity. Some women have decreased vaginal lubrication. This problem is likely the result of the interruption in normal nerve signals from the brain to the genital area.

Typically, lubrication occurs as a mental and physical reflex response to something sexually stimulating or arousing. Lubrication is a sign of sexual arousal and generally results in easier vaginal penetration and more pleasurable sexual activity. While most women with SCI maintain some degree of lubrication, those who wish can utilize a waterbased lubricant (never use oil based lubricants), such as K-Y Jelly, to facilitate sexual activity.

Depending on your level and completeness of injury, you may experience a change in surface sensation and ability to contract your muscles. This may lead you to try sexual positions or activities different from those prior to your injury. Talking to your partner about your need and/or desire for these new activities and positions is also a way to improve your relationship.

One of the changes that you may notice after SCI is that it takes longer for an orgasm to occur and/or it feels different. While the majority of women with SCI are able to experience orgasm, it may take more stimulation than prior to injury. Also, many of the medications that women take can make it more difficult to achieve orgasm.

If you are having difficulties, the use of a vibrator may help women with an injury below the T6 level. It may also be helpful to speak with your physician to see if your medications could be adjusted to minimize their impact on your sexual responses.

Fertility

It is normal for most women to experience a brief pause in their menstrual cycle after SCI. This pause may last as long as six months after the injury. However, a study from the UAB Model SCI System (Jackson, 1999) showed that the ability of women to have children is not usually affected once their period resumes. If your period does not resume, talk to a doctor about possible options for treatment.

Sexual Adjustment

Women who know the facts about living with SCI understand that the loss of movement or sensation does not mean a loss of pleasure. Women with SCI can, and do, resume active, enjoyable sex lives after injury.

Issues with body image can be a primary area of concern (see Table 1). It is important because how you feel about yourself will influence your desire to engage in sexual activity, and your partners desire as well. A positive attitude and a little humor will naturally attract others to you and will help you feel good about yourself.

One of the main keys to adjustment is learning to manage impairment related issues of everyday life. All women have doubts, concerns and questions, so it is normal for women with SCI to feel the same way. However, the facts are simple. Women with SCI:

- are desirable;

- have the opportunity to meet people, fall in love, and marry;

- are sexual beings;

- have sexual desires;

- have the ability to give and receive pleasure;

- can, and do, enjoy active sex lives; and

- can become pregnant and have children.

Women who accept these facts as true will find it easier to achieve a satisfying and happy sexual relationship.

You and Your Partner

Many women worry about whether or not they can maintain a relationship after injury. In reality, it is impossible to predict the success of any relationship. Lasting relationships depend on a number of factors such as personal likes and dislikes, common interests and long-term compatibility. All relationships take hard work, dedication and commitment.

Women with SCI need to help their partners understand the issues of spinal cord injury and the areas of concern. Communicate clearly and work together to solve problems. This is a great way to build physical and emotional intimacy.

Areas of Concern

Table 1 ranks ten common areas of concern for women with SCI. While these concerns may be more common right after injury, these are life long issues that may always need special attention. The best way to feel good about these concerns are to discuss them with your partner ahead of time, be aware of what could happen and be prepared to deal with any problems that arise. In time, you and your partner will become more at ease in dealing with these issues.

Bladder management is a concern for most women with SCI. There are a number of ways to reduce the chance of urinary accidents during sexual activities. First, women might limit fluid intake if they are planning a sexual encounter. Drinking too much fluid increases urine output and causes the bladder to fill more quickly. Women who use intermittent catheterization for bladder management can empty their bladder before engaging in sexual activity. Women who use a Suprapubic or Foley catheter may have concerns about the tubing. The Foley can be left in during sexual intercourse because the urethra (urinary opening) is separate from the vagina. If the catheter tube is carefully taped to the thigh or abdomen so that it will not kink or pop out, it should not interfere with intercourse. Women also have the option of removing the Foley catheter before sexual activities, but the catheter needs to be properly reinserted following sexual activities.

Bowel management is another concern for women with SCI. The best way to avoid accidents is to establish a consistent bowel management program. Once a routine is established, an accident is much less likely to occur. For added confidence, empty your bowel and avoid eating before sexual activity.

Sexual satisfaction may be an issue for some women who wonder whether or not they can be sexually satisfied or satisfy a partner. Talking to your partner, experimenting with new ideas and working together will help you find mutual satisfaction.

Sexual exploration can also help couples enhance their physical pleasure. The goal is to find sexual activities that are interesting, enjoyable and mutually pleasurable. As couples work together, it may help to try different methods of giving and receiving physical pleasure. Some couples may find that methods for gaining sexual satisfaction are the same as before injury. However, those "old" methods may not be satisfying. Sexual exploration can help you and your partner enhance your physical pleasure. The goal is for both you and your partner to gain mutual satisfaction. Hopefully, you will then find that sexual activity is interesting and enjoyable. It may also be necessary for some couples to explore a variety of sexual positions to find comfort during sexual intercourse. This exploration may be needed especially if spastic hypertonia (muscle spasms or contractures) or pain occurs during sexual activities. If spastic hypertonia or pain is a problem, it is recommended that you talk to a doctor for advice on treatment.

Sexual arousal is the emotional and physical process of stimulating excitement and readiness for sexual activity. Emotionally, you will likely find that you are still aroused by the same things as before your injury. These emotionally stimulating activities might include dressing up, a romantic dinner, showering together or an erotic film. This is another opportunity for sexual exploration. It may help to know what other women with SCI find physically arousing. Also, it is often helpful to "explore" your body and see what works before being sexually active with a partner. Women have reported they can achieve arousal through their mouth and lips, neck and shoulder, clitoris, stomach, vagina, thigh, breasts, buttocks, ears and feet.

Other Potential Problems

Autonomic Dysreflexia (AD) is a life-threatening condition for women at the level of T-6 injury and above. Although sexual activity normally results in a rise in blood pressure, which is one sign of AD, women at risk and their partners should be watchful for other signs such as irregular heart beat, flushing in the face, headaches, nasal congestion, chills, fever, blurred vision, and/or sweating above the level of injury. While AD has not been noted in lab studies of sexual response in women with SCI, if you experience multiple signs of AD during sexual activity stop immediately. If symptoms continue after stopping, it is crucial to contact a doctor immediately for advice.

Verbal and physical abuse is an unfortunate reality in some relationships. Women who are in an abusive relationship can talk to friends, family, doctors or clergy to find local agencies that help women escape abusive relationships. Seek help from the agency of your choice. However, if needed, the National Domestic Violence Hotline is 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or TTY 1-800-787-3224.

Sexual Dysfunction in women is gaining interest in the medical community. For women with SCI, dysfunction is most often a lack of desire to participate in sexual activities or a failure to achieve satisfaction. There are treatment options available, so talk to your doctor if you think sexual dysfunction might be impacting the quality of your sex life.

Aging can impact sexuality. Many women have a decline in sexual interest and a decrease in vaginal lubrication after menopause. It is worthwhile to discuss these issues with your doctor because in some cases medications may be prescribed to assist with these problems. Although it is natural to experience some changes in sexuality over time, there is no reason why you cannot continue to enjoy an active sex life as you age.

Conclusion

Sexuality does not have to change after spinal cord injury. Women with SCI can still express sexuality both physically and emotionally. However, it is important for women to learn how their injury may have changed their mind and body. When you prevent potential problems and properly manage areas of concern, you will feel comfortable in exploring, expressing, and enjoying all aspects of sexuality regardless of your level of injury.

If needed, women with SCI should not hesitate to get professional advice if they experience problems related to sexuality. For example, a professional counselor can help resolve problems with self-adjustment and relationship issues. A physiatrist (doctor who specializes in rehabilitation medicine) can be an educational resource for women and help them manage medical issues. Plus, a physiatrist can likely recommend a urologist and gynecologist knowledgeable on issues related to sexual and reproductive health for women with spinal cord injury.

References:

-Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Response. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Co Inc, 1966.

-Bors E, Comarr EE. Neurological disturbances of sexual function with special reference to 529 patients with spinal cord injury. Urol Surv. 1960;110:191-221.

-Sipski ML, Alexander CJ, Rosen RC. Sexual arousal and orgasm in women: effects of spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:35-44.

-Sipski, ML, Alexander, CJ. Sexual activities, response and satisfaction in women pre- and post-spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1993;74:1025-1029.

-Jackson AB, Wadley V. A multicenter study of women's self-reported reproductive health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med & Rehab 1999;80(11):1420-1428.

-McClure, S. Female sexuality and spinal cord injury. Arkansas Spinal Cord Injury Association Fact Sheet #8, 1992

-Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Menter RR, et al. Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1992;30:192-199

-White, MJ, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ. Sexual activities, concerns and interests of women with spinal cord injury living in the community. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 1993;72(6):372-378.

-Benevento BT, Sipski ML. Neurogenic bladder, neurogenic bowel, and sexual dysfunction in people with spinal cord injury. Physical Therapy, 2002;82(6):601-612. Review.

Resources:

Secondary Conditions of Spinal Cord Impairment Health Education Video Series - Sexuality and Sexual Function (2006)

Free video download from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Model SCI System. Online at: http://www.spinalcord.uab.edu/show.asp?durki=97417

A 3 DVD series, sold only as a set, is available by mail. Total cost is $30. Make check payable and send to: UAB Office of Research Services, 619 19th St S, SRC 529, Birmingham, AL 35249-7330

Enabling Romance: A Guide to Love, Sex, and Relationships for People with Disabilities (and the People who Care About Them) By Ken Kroll and Erica Levy Klein, book, approx 220 pages, available for purchase online, $15.95 plus S&H:

https://www.newmobility.com/bookstore-romance.cfm?type=REG&order_id=newtype=REG&order_id=new

Or contact No Limits Communications, Inc. at (888)850-0344

SexualHealth.com

This website provides information about the ways in which different kinds of spinal cord injuries can affect sexual relationships and functioning.

http://www.sexualhealth.com/channel.php?Action=view_sub&channel=3&topic=11

Spinal Cord Injury Manual

A free online publication from the Thomas Jefferson University Regional Spinal Cord Injury Center of Delaware Valley (includes a section on Sexuality). Available online at:

http://www.spinalcordcenter.org/manual/index.html

To inquire about mail service call (215) 955-6579

Spinal Cord Injury: Sexuality

Article from the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago LIFE Center, reviewed November 2006. Available free online at:

http://lifecenter.ric.org/content/2560/?topic=3&subtopic=163#pagetop

Or contact (312) 238-LIFE (5433)

Sexuality Reborn

Video available for purchase from Kessler Medical Rehabilitation Research & Education Center. Online order form at:

http://www.kmrrec.org/nnjscis/consumer.php?cnav=5

Or call (973) 243-6812

Through the Looking Glass

A nationally recognized center that has pioneered research, training and services for families in which a child, parent or grandparent has a disability or medical issue.

http://lookingglass.org/

2198 Sixth Street, Suite 100, Berkeley, CA 94710-2204

1-800-644-2666 (VOICE)

The National Domestic Violence Hotline

http://www.ndvh.org

If something about your relationship with your partner scares you and you need to talk, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at:

1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or 1-800-787-3224 (TTY)

Dating & Relationships after SCI

Free online SCI Forum Report from the University of Washington NW Regional SCI System. Available online at:

http://sci.washington.edu/info/forums/reports/dating.asp

Or contact (206) 685-3999

Published by:

The University of Alabama Model SCI System

Office of Research Services

619 19th Street South, SRC 529

Birmingham, AL 35249-7330

(205) 934-3283

Email: sciweb@uab.edu

Date: Revised November 2007

Developed by: Phil Klebine, MA

Contributions by: Linda Lindsey, MEd; Patricia Rivera, PhD, and Marca L. Sipski-Alexander, MD

Edited by: Shirley Estill, BS

© 2007 Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama at Birmingham provides equal opportunity in education and employment.

3.3. Pregnancy and Women with SCI

"Pregnancy and Women with SCI" - Professional Level

Date: January, 1998

Developed by: Amie B Jackson, MD and Linda Lindsey, ME

Many women who receive spinal cord injuries are in their childbearing years. Following a spinal cord injury (SCI), there is no evidence that a woman's ability to conceive is affected. Observation has shown however, that women with SCI are usually older when they have their first pregnancy, than their able-bodied counterparts and therefore may have age related fertility issues.

Women with SCI do have unique obstetrical challenges. With increased awareness and support however, these women can have maternal experiences similar to their able-bodied counterparts.

One of the biggest problems reported by women during this time is finding a physician who understands their situation and is willing to learn about their unique bodies. Women with SCI have special concerns regarding the effects of pregnancy on their disability as well as the disability on their pregnancy. Obtaining information and allowing communication between the woman and her physician prepare all for the many changes to come.

- Before Conception

When possible, it is important for the woman to discuss her plans for starting a family with her physician. Some medical concerns to address prior to conception are:- Medications

Review each medication that the woman is taking to evaluate any potential for birth defects. If possible, drugs should be discontinued, especially during the first 3 month of pregnancy. - Urological Evaluation

X-rays should not be done during pregnancy unless absolutely necessary, as they could harm the fetus. Schedule a complete urologic evaluation and consult with the urologist regarding the type of urologic follow-up care that is advisable during pregnancy. - Physical Changes

Some women may have a skeletal abnormality, i.e., curvature of the spine, pelvic fractures or hip disarticulation. These can interfere with the space in the abdomen available to carry a full-term fetus or have a normal delivery. Advise the woman of any complications she may experience.

- Medications

- Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a time for planning and change for all women, however this becomes more critical for a woman with a disability. The growing fetus may potentiate the physical limitations of the woman with a spinal cord injury. Fetal/uterine enlargement may affect diaphragm movement, diminishing respiratory capacity and predisposing these women to pneumonia, especially those with tetraplegia.In addition, pressure ulcers are more likely to occur as pressure relief and transfers become more difficult secondary to the mother's changing weight. Furthermore, changing nutritional demands and the mother's altered center of gravity can impair healing to a pressure ulcer once it develops. Pregnancy enhances a woman's susceptibility to anemia, which may also contribute to skin breakdown.

Programs for neurogenic bowel and bladder may also be affected as the fetus grows. Constipation is a problem during pregnancy for all women due to delayed movement of food through the bowel from hormonal effects and iron supplementation. The pressure from the growing fetus/uterus on the bladder may cause incontinence. Bladder spasticity may increase with similar consequences.

Urinary tract infections increase more than usual due to the increased susceptibility that pregnancy causes. Chronic antibiotic supression may be advocated at specific times during all trimesters.

Another possible concern from the growing fetus is increased pressure on the venous return from the legs. This may predispose the woman to developing a blood clot in her legs (called deep venous thrombosis - DVT).

The woman likely will require more help with daily living activities. Review her independent skills and how these are changing during the pregnancy. This may require authorizing services such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, or home care.

- Labor and Delivery

Indications for vaginal deliveries vs. Cesarean section are essentially the same for women with spinal cord injuries as with able-bodied women. Research has shown however that C-sections are more frequently performed in women with SCI. The uterus, controlled by neurohormonal factors and not neurological factors, begins the contractions at the appropriate time. This is the same for women regardless of motor function and sensory level.Women with injury above the level of T10 will not have sensation of uterine contractions. Women are able, however, to use other indicators for labor such as fear and anxiety, increased spasticity, respiratory changes, referred pain above the level of injury or autonomic dysreflexia (AD). It is important to watch for signs of AD at all times during labor and delivery. (Severe headaches, high blood pressure, flushing, sweating).

- Psychological